SIM – Strategic Investment Map

I would like to introduce you to an alternative to the Victorian Government’s Investment Logic Map (ILM) called the Strategic Investment Map or SIM.

- Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but SIM is not an imitation, it is an evolution based on my years of experience in strategic planning and business case development.

- SIM, like ILM and many other frameworks, is grounded in systems thinking and common sense.

- SIM aims to address the feedback and lessons learned on the many ILM-type workshops that I have led and been involved in.

What is a Strategic Investment Map, or SIM?

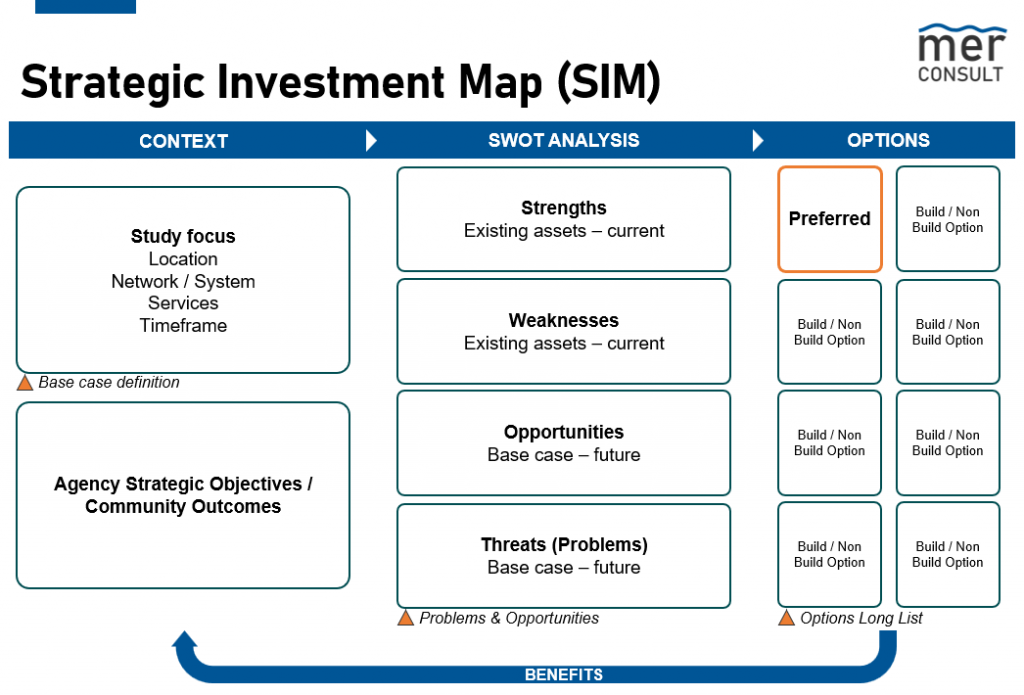

- Part 1 of a SIM starts with Context, which includes a summary of high-level community outcomes – these are needed because they frame the focus area of the analysis. They should exist already, e.g. in a strategic plan. Are we solving the World or are we looking at a specific set of outcomes, such as an agency’s strategic objectives? This is aligned with ATAP by the way (see glossary below for acronyms).

- Also in Part 1 is a brief definition of the study focus. It could be a physical location, or corridor (study area), or it could be a network of assets (like a water distribution network, or a transport system). It will also define the study timeframe; how far into the future are we trying to look? This step is critical to establish the ‘base case’.

- Part 2 is similar to other models – it’s a summary of problems and opportunities – but I have expanded that to include a SWOT analysis (Strengths and Weaknesses look at the present, Opportunities and Threats look ahead). Many investment frameworks (like SAMF here in WA) emphasise the need to understand existing assets but this isn’t always done very well in the rush to conceive a new asset. I think its critical, especially as we try to make better use of existing assets before building new ones. I also like to explicitly include Opportunities rather than asking my workshop participants to do mental gymnastics and convert them into problems. I think Threats is more of a risk-based approach than Problems, so it recognises inherent uncertainty in projecting forward.

- Part 3 is response options that have the potential to address the problems (or threats) and opportunities. Compared to ILM, the map skips Benefits and KPIs. These are important but in my experience people struggle with this part, especially KPIs, and it disrupts the flow of logic. Having outcomes on the map (from Step 1) helps a lot because you can check that there is clear alignment between Options, Problems and Outcomes (the return arrow at the bottom of the map).

- Including a range of potential Options helps us cut to the chase and this is a major departure from ILM. Options can still be high-level strategic responses and they should definitely include non-build options where appropriate. If there is an initial preference this can be noted in the map very easily, but you could also just leave it as a ‘long list’ for further analysis.

In summary, there are only three parts and it can be done in a single workshop – ideally two but with the same scope so that the second one is more of a validation and improvement than a different part of the analysis.

SIM provides a rapid plan on a page – but it can also be supported by separate analyses to support the summary and to capture details and rationale – basically the thinking behind the summary map. This sets you on the path to further analysis and ultimately all of the information needed to make a robust investment decision. The real value of SIM comes from getting the key people in a room (or on Teams!) to develop a rational hypothesis before investing resources in detailed analysis.

A key outcome of the SIM is a very (and I mean very) high level picture of a potential initiative / investment in a short space of time. This could form the basis of an ACA or some other early stage proposal as required by IWA’s MIPA guidelines. Many infrastructure investment frameworks call for the early identification of a potential solution so why not cut to the chase and use SIM at the very start of your next infrastructure investment planning process?

Infrastructure acronym heaven:

- ATAP = Australian Transport Assessment and Planning

- IAAF = Infrastructure Australia Assessment Framework

- ILM = Investment Logic Map, or Investment Logic Mapping

- IWA = Infrastructure WA

- MIPA = Major Infrastructure Proposal Assessment

- SAMF = Strategic Asset Management Framework

- SIM = Strategic Investment Map, or Strategic Investment Mapping

- SWOT = Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats

Five tips for successful infrastructure business cases

As posted in LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/five-tips-successful-infrastructure-business-cases-marcus-rooney/

Infrastructure has incredible potential to transform regional and urban economies whilst delivering important social and environmental benefits, creating jobs, and stimulating economic activity. In Australia, investment in the transport sector alone (road, rail, ports, etc.) has been nearly $20 billion per year since 2000 (www.data.oecd.org). Public infrastructure is mostly funded by different levels of government through taxes and rates, supported by user charges in some sectors.

Given the opportunity and the amount being spent, it is vital that limited resources are spent wisely.

The basic economic principle is that benefits must outweigh the costs, so you just add them up and there you go… Easy? Not really… actually very difficult. Some of the main reasons are:

1. Infrastructure benefits are distributed over a much longer period than costs. Infrastructure has a relatively short ‘design and build’ period followed by a much longer ‘operate and maintain’ period when most of the benefits occur. Longer term impacts are harder to predict and sensitive to assumptions like escalation and discount rates.

2. Some benefits are hard to measure and hard to explain. Public infrastructure often has a minimal link between use and funding, so you often have to dig quite deep to find quantifiable benefits. This can involve extensive debates about concepts like consumer surplus, externalities, non-monetized impacts and productivity. Secondary impacts are even harder, for example land use impacts related to transport projects, which is a topical challenge for light rail and trackless trams.

3. Many things will change over the life of the asset that will impact – and be impacted by – the project such as demographics, disruptive technologies, what happens to adjacent infrastructure and changing economic conditions. This makes it very difficult to isolate the specific impact that the project will have versus what might have happened anyway without the project.

4. The art and science of infrastructure business cases is limited by the lack of available data on what has worked in the past, clear relationships between asset provision and service outcomes, and the extent to which expected benefits have materialised.

5. How can we look back and determine whether an alternative project would have had a greater impact at the same or even lower cost …? Alternatives can usually only be developed at a high-level due to time and cost constraints. What if light rail or trackless tram had been a better solution than buses on congested roads? An interesting sidenote is the incentive (some would say bias) of the organisation developing the business case and the role of political commitments… but that is a topic for another day.

Business cases take time to develop because they need to try and address these issues, and more. Only then can our public sector officers can make sound recommendations, and our elected representatives can make the big decisions.

Having worked on a few infrastructure business cases, my top tips for success are:

1. Establish very clear project purpose and objectives. Infrastructure has the potential to deliver many types of benefits over many years but there should only be one or two fundamental reasons for delivering the project in the first place. In other words, there is a difference between purpose and impacts. All impacts should be assessed, but only the purpose should drive the design, and be the definition of success. The purpose and objectives should be based on specific problems and/or opportunities.

2. Quantify problems and opportunities at a strategic level. In an ideal world, organisations responsible for services and outcomes would be continuously using operational data and customer-based measures to rapidly identify emerging problems. They would also be scanning emerging technologies and circumstances that could give rise to opportunities to improve outcomes and/or deliver services more efficiently. These activities are at what I call the “strategic level” and differ from what sometimes ends up happening, which is a much narrower study area defined by a project that has already been proposed. Organisations that have truly embraced Strategic Asset Management will already be doing this.

3. Clearly define the base case. The base case is essentially the study area without the project. It has two major functions: (1) to establish the future problems and opportunities, and (2) to compare to the project, and alternative options. Infrastructure Australia have typically required a strict base case in which you cannot assume any other major infrastructure developments, but this position is changing. A pragmatic view is needed to make some assumptions about what is likely to happen in the future without the project. This can be difficult because very few projects are not somehow connected to existing assets, users, and a whole range of potential impacts. In my experience, this has led to a need for several potential alternative base cases, or scenarios. Although it requires a bit of work it often reveals very valuable insights into infrastructure strengths, weaknesses, and risks.

4. Do some (good) modelling. To estimate longer term costs and benefits you need to have a sound understanding of demand for the service that the proposed infrastructure is going to enable, whether that’s water consumption, peak power demand, or in-patient treatments. You have to model the base case (see above) and the project case(s) and compare them to quantify the various impacts. Apart from the obvious difficulty of predicting the future, there are many uncertainties to try to consider such as changing service models (water conservation, rooftop solar, telehealth, etc.) and mega-trends (drying climate, carbon capture, aging population, etc.). Modelling can be a complex process and relies on good data. This is a huge opportunity area for many infrastructure sectors.

5. Look beyond the Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR). Methods and data for estimating economic costs is far more advanced than on the benefits side of the equation. Established methods are available but these tend to focus on economic impacts such as travel time savings, reduced user costs and avoiding future costs. Social and environmental impacts are harder to measure, and some methods rely on international parameters – but that does not mean they should be ignored. There is increasing advocacy for a greater focus on the social value of infrastructure, including by Consult Australia, and there are rumours that the updated Infrastructure Australia Assessment Framework will also recognise this important trend.

Did you notice that many of the points above are related? This leads to my final suggestion, which is that business cases ultimately represent a flow of investment logic. Good business cases have a central narrative that picks up on all these issues and addresses them concisely. There are various frameworks out there to help establish this logic and help frame the case for change.

A quick note on skills: business case development is a truly multi-disciplinary effort requiring inputs from a broad range of professionals. A strategic planning mind-set is almost as important as technical expertise. A strong client team is essential to set the experts off on the right path, coordinate workstreams and ultimately lead the production of a fully integrated and well-constructed business case.

What are your business case experiences? Do any of these issues strike a chord?

If you would like to discuss further, let me know!